‘LLM Agents and Security’ in Linux Magazin 01/2026¶

Systems with LLM agents pose particular security challenges. The fundamental weakness of LLMs is that they cannot strictly separate instructions from data, meaning that all data they read could potentially be instructions. This leads to the ‘lethal trifecta’ of sensitive data, untrustworthy content, and external communication—the risk that an attack will occur via hidden instructions read by an LLM, which then passes on sensitive data. We must take explicit measures to mitigate this risk by minimising access to each of these three elements. It makes sense to run LLMs in controlled containers and divide tasks so that each subtask blocks at least one of the three elements. Above all, small steps should be taken that can be controlled and verified by humans.

Introduction¶

Large Language Model (LLM) agents offer a radically new way to develop software by coordinating an entire ecosystem of agents through imprecise conversation. This is a completely new way of working, but it also poses significant security risks.

We simply don’t know to defend against these attacks. We have zero agentic AI systems that are secure against these attacks. Any AI that is working in an adversarial environment – and by this I mean that it may encounter untrusted training data or input – is vulnerable to prompt injection. It’s an existential problem that, near as I can tell, most people developing these technologies are just pretending isn’t there.

– Bruce Schneier: We Are Still Unable to Secure LLMs from Malicious Inputs [1]

To keep track of these risks, we comb through research articles that have a deep understanding of modern LLM-based tools and a realistic view of the risks. To help our teams at cusy, we regularly write about this in our blog [2], summarising this information. Our goal here is to provide an easy-to-understand, practical overview of security issues and mitigation measures related to agent-based LLMs. With this article, we want to make our thoughts available to a wider audience.

The content is based, among other things, on extensive research by experts such as Simon Willison [3] and Bruce Schneier [4]. There are many risks in this area, and it is changing rapidly – so we need to understand the risks and figure out how to mitigate them wherever possible.

What do we mean by ‘agential LLMs’?¶

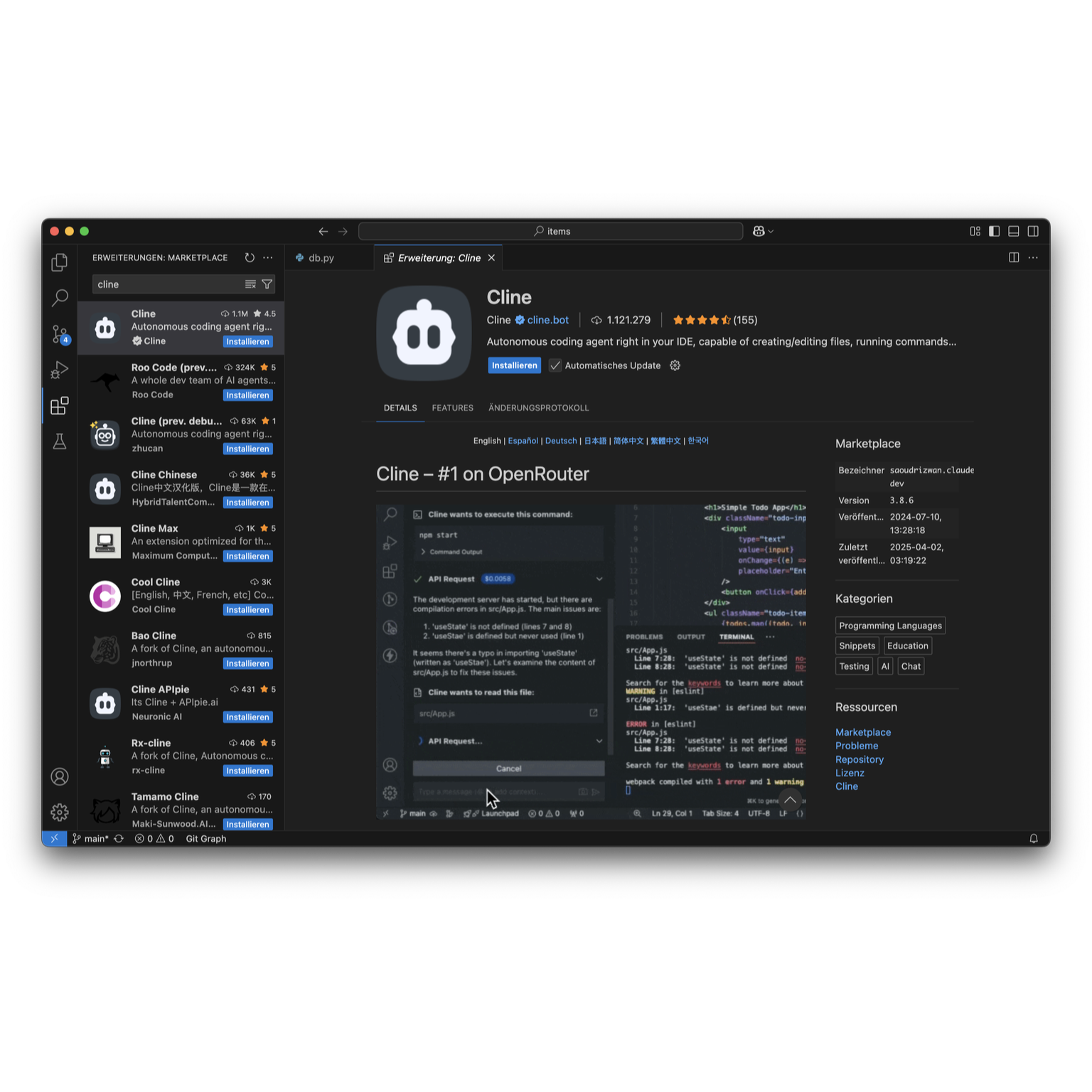

Technology is changing rapidly, making it difficult to define terms. AI in particular is overused to describe everything from machine learning [5] to large language models [6] to ‘artificial general intelligence* [7]. Essentially, we are talking about ‘LLM-based applications that can act autonomously’, meaning applications that extend the basic LLM model with internal logic, loops, tool calls, background processes, and sub-agents. Initially, these were mainly programming assistants such as Claude [8], Cline [9] or Cursor [10], but increasingly it is almost every LLM-based application. It’s helpful to clarify the architecture and functioning of these applications. An agentic LLM reads from a large number of data sources and can trigger activities with side effects:

The architecture of agentic LLMs¶

graph TB

Userprompt[User prompt] --> AgenticLLM

AgenticLLM --> TextResponse[Text response]

AgenticLLM -->|query| ReadActions[Reading actions

• Search the web

• Read code

• MCP server]

ReadActions --> |reply| AgenticLLM

AgenticLLM --> |execute| WriteActions[Writing actions

• Modify files

• HTTP calls

• Shell commands

• MCP server]

WriteActions --> |reply| AgenticLLM

WriteActions --> |write| External[External]

subgraph AgenticLLM[Agentic LLM]

SessionContext

SystemContext[System context]

TrainingData[Training data]

SessionContext[Session context]

end

Some of these agents are explicitly triggered by the user, but many are integrated. For example, programming applications typically read the project source code and configuration without informing the user. And the more intelligent the applications become, the more agents are active in the background.

What is an MCP server?¶

An MCP server is actually a type of API that has been specifically designed for use with LLMs. The Model Context Protocol (MCP) [11] is a standardised protocol for these APIs, so that an LLM understands how to call them and what tools and resources they provide. The API can provide a variety of functions – for example, it can call a script that returns read-only static information, or it can connect to a web-based service such as GitHub. It’s a very flexible protocol.

Map and secure MCP integrations¶

Get an overview of all MCP servers in use and only use those from trusted sources. Map the connected data sources for each MCP server and check whether they originate from external systems that could cause untrusted input.

What are the risks?¶

Applications such as Claude typically have numerous control mechanisms in place – for example, Claude does not read files outside of a project without permission. However, Claude can be persuaded to create and execute a script that reads a file outside of a project. Once an application is allowed to execute arbitrary commands, it is very difficult to block certain tasks afterwards.

The core problem – LLMs cannot distinguish content from instructions¶

LLMs always work by first creating a large text document and then continuously completing it. What appears to be a conversation is just a series of steps to expand this document. LLMs are amazingly good at taking this large block of text and using their extensive training data to create the most appropriate next block of text.

Agents also work by adding further text to this document – if the current prompt is ‘Please review the current merge request’, the LLM knows that this is a request to analyse specific code changes. It queries the Git server, extracts the text changes, and adds them to the context.

The problem here is that the LLM cannot always distinguish between different texts – it cannot distinguish data from instructions. LLM verification is random and non-deterministic: sometimes an instruction is recognised and executed, especially if a malicious actor designs the payload in such a way that it is unlikely to be detected. Thus, our question ‘Please review the current merge request’ – where the merge request was created by a malicious actor – can result in private keys, environment variables, etc. being leaked. This is basically how prompt injection works.

Lethal Trifecta¶

This brings us to Simon Willison’s article The lethal trifecta for AI agents [12], which highlights the biggest risks of agent-based LLM applications:

- Access to private data

one of the most common uses of tools in general

- Access to untrusted content

any mechanism through which text controlled by a malicious attacker could become available to the LLM

- Ability to communicate externally

In a way that could be used to steal private data

If all three factors apply, there is a high risk of attack. The reason for this is quite simple:

Untrusted content may contain commands that the LLM may execute.

Sensitive data is the main target of most attackers – this can include, for example, private keys that allow access to private data.

External communication allows the LLM application to send information back to the attackers.

Here is an example from the article ‘AgentFlayer: When a Jira Ticket Can Steal Your Secrets’: [13]

A person uses an LLM to search Jira tickets via an MCP server.

Jira is set up to automatically populate itself with Zendesk tickets from the public domain → untrustworthy content.

An attacker creates a ticket that is carefully designed to ask for ‘long strings starting with eyj’, which is the signature of JSON Web Token (JWT) → sensitive data.

The ticket asked the user to log the identified data as a comment on the Jira ticket, which was then visible to the public → external communication.

What at first glance looked like a simple query becomes an attack vector.

Remedy¶

So how can we reduce our risk without sacrificing the performance of LLM applications? Eliminating just one of the three factors listed below significantly reduces the risks.

Minimise access to sensitive data¶

Completely avoiding access to sensitive data seems almost impossible. Using

.cursorignore [14] files or similar mechanisms to exclude sensitive

files and directories from processing by agents only lulls us into a false sense

of security: when LLM agents run on our development computers, they usually have

access to things like our source code, which is still allowed to read sensitive

files. However, we can actually reduce the risk by limiting the available

content:

We never store our deployment credentials in a file, as LLMs can easily be tricked into reading such files.

We use utilities such as KeePassXC [15] to ensure that credentials are only stored in memory and not in files.

We also use temporary privilege escalation to access production data.

We restrict access tokens to just enough permissions – read-only tokens pose a much lower risk than tokens with write access.

We avoid MCP servers that can read sensitive data. If this seems unavoidable, we describe further remedial measures later.

We are very cautious with browser automation: for example, we ensure that Playwright MCP [16] runs a browser in a sandbox without cookies or login details. However, others do not allow this – such as the Playwright browser extension, which connects to our browser and allows access to all our cookies, sessions and browsing history.

Block external communication¶

At first glance, this sounds like an easy task: preventing agents from sending emails or chatting. However, this can also cause a number of problems:

Any internet connection can transmit data externally. Many MCP servers offer options that can lead to information being made public. ‘Responding to a comment on a problem’ seems safe until we realise that this could make sensitive information public.

If agents can control a browser, they can also publish information on a website. But there are many more of these so-called exfiltration attacks. [17]

Restricting access to untrustworthy content¶

We usually try to avoid reading content that can be written by the general public – that is, no public issue trackers, no random websites, no emails. We declare all content that does not come directly from us as potentially untrustworthy. We could ask an LLM to summarise a website and then hope that this website does not contain any hidden instructions in the text, but it is much better to limit our request: ‘Summarise the content of www.cusy.io’. We usually create a list of trusted sources for the LLM we are using and block everything else. In situations where we need to research potentially untrustworthy sources, we separate this risky task from the rest of our work – see Splitting up the tasks.

Nothing should violate all three points of the Lethal Trifecta¶

Many popular applications and tools are allowed to access untrusted content and sensitive data and communicate externally – these applications pose a huge risk, especially since they are often installed with autostart enabled. Instead, we only allow them in isolated containers.

One example of this is LLM-based browsers or browser extensions – wherever they can use a browser that can utilise login details, sessions or cookies, they are completely unprotected.

I strongly expect that the entire concept of an agentic browser extension is fatally flawed and cannot be built safely.

– Simon Willison [18]

Nevertheless, providers continue to promote LLM-based browsers. A few weeks ago, another report on invisible prompts in screenshots [19] was published, describing how two different LLM-based browsers were tricked by loading an image onto a website that contained low-contrast text that was invisible to humans but readable by the LLM, which treated it as an instruction.

We therefore never use such browser extensions. At best, we use the Playwright MCP server, which runs in an isolated browser instance and therefore has no access to our sensitive data.

Sandboxing¶

Several of the recommendations listed here relate to preventing LLMs from performing certain tasks or accessing certain data. However, most LLM tools have full access to a user’s computer by default – they do try to minimise risky behaviour, but these measures are not ideal. An important risk mitigation measure is therefore to run LLM applications in a sandbox – an environment where we can control what they can and cannot access. Some tool providers are working on their own mechanisms for this: for example, Anthropic recently announced new sandboxing features for Claude Code, [20] but the most proven method is still to use a container.

Our LLM applications run within a virtual machine or container whose access to external resources can be precisely restricted. Containers have the advantage that we can control their behaviour at a very low level – they isolate our LLM application from the host machine, allowing us to easily block file and network access. Although there are sometimes ways for malicious code to escape from a container, [21] these currently appear to pose a low risk for common LLM applications.

In the following, we will take a closer look at three different scenarios for LLMs in containers.

Scenario 1: Running the LLM in a container¶

A container can be set up with a virtual Linux machine, which we then log into

via SSH and run a terminal-based LLM application such as Claude Code [22] or

Codex CLI [23]. An example of this approach can be found in the

claude-container repository [24]. To integrate our source code into the

container, we use so-called multi-stage builds [25]: First, we create an

app Dockerfile with our source code, which we then transfer to our

runtime container:

COPY . /app/

COPY --from=build --chown=app:app /app /app

USER app

WORKDIR /app

First, we copy our application to the runtime container and then change the permissions for the service user and the app group. Complete instructions for our multi-stage builds can be found in ‘Python Docker Container with uv’ [26].

Scenario 2: Running an MCP server in a container¶

Local MCP servers are usually run as a subprocess, using a runtime environment such as Node.js or even executing any executable script or binary file. Unless the MCP servers use LLMs internally, their security is equivalent to that of any third-party applications whose authors we trust. However, some MCPs do use LLMs internally, and in that case it is still a good idea to run them in a container. However, running an MCP server in a container does not protect us from the server being prevented from inserting malicious prompts. So, putting a GitHub Issues MCP server in a container does not prevent issues created by malicious actors from being treated as instructions by the LLM.

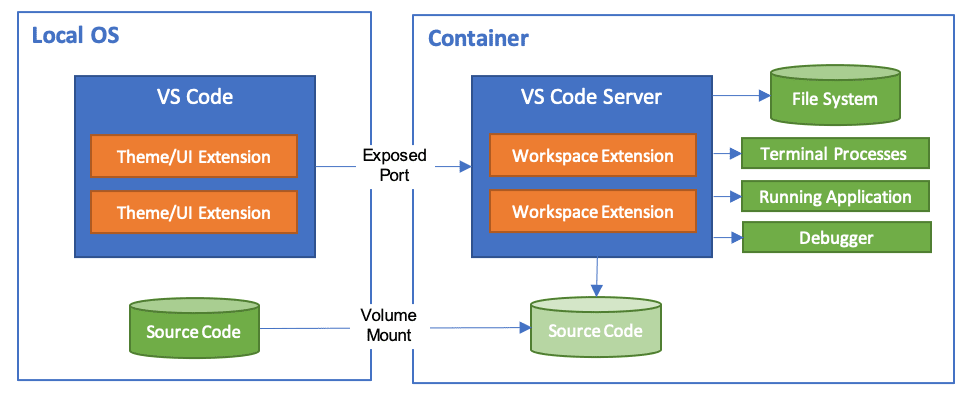

Scenario 3: Running the entire development environment in a container¶

There is an extension [27] for Visual Studio Code that allows the entire development environment to be run in a container:

Anthropic provides a reference implementation for running Claude Code in a dev

container. [28] This includes a firewall with a list of accepted domains, which

can be used to control access more precisely. However, the

–dangerously-skip-permissions option is used by default, which means that in

the event of an attack, the login details for Claude Code could also be

obtained.

Splitting up the tasks¶

One way to minimise the risks of the Lethal Trifecta is to split the work into several phases, each of which is more secure. This allows us to split the work into tasks that only use part of the Lethal Trifecta and only receive the permissions that are currently needed.

Every program and every privileged user of the system should operate using the least amount of privilege necessary to complete the job.

– Jerome Saltzer, ACM [29]

By dividing the work and assigning minimal privileges for each subtask, the scope for attacks is reduced. However, this is not only more secure, but also recommended for other reasons: LLMs work much better when their context is not too large. Dividing the tasks reduces the context.

Strict data formatting¶

Instead of allowing arbitrary text generated by LLMs, we restrict it to conform to a precisely defined JSON or XML schema. Such restrictions can be applied algorithmically to the output of an LLM [30], which is now supported by several open-source libraries and in the APIs of commercial LLM providers. [31] Format validation can be implemented as a fallback.

We humans remain in the game¶

Artificial intelligence makes mistakes, it hallucinates, and it can easily cause slop and technical debt. It can also be easily exploited for attacks. It is therefore crucial that a human reviews the processes and results of each LLM phase.

The tasks should be performed in small interactive steps with careful control over the use of tools. LLMs should not be blindly given permission to run any tool. Every step and every result should also be reviewed.

Even though this runs counter to the goal of automating tasks through agents, we rely on our judgement for non-time-critical tasks in order to increase security. However, we are limited by our working hours and must also avoid mental fatigue [32]. The developer experience is crucial here, as in the worst case scenario, we may find the query obstructive and no longer read the information provided [33]. Furthermore, the intersection between suggestions and judgement can become too complex, often resulting in valuable feedback from people with high technical expertise being ignored, while laypeople often rely too heavily on algorithmic results [34].

Nevertheless, it is our responsibility to check all output for faulty code, manipulated content and, of course, hallucinations.

We, the developers of the software, are responsible for the code and all side effects – the AI tools cannot be blamed for this. In ‘Vibe Coding’, the authors use the metaphor of a developer as a head chef overseeing a kitchen with AI sous chefs. If a sous chef ruins a dish, the head chef is responsible.

When the customer sends back the fish because it’s overdone or the sauce is broken, you can’t blame your sous chef.

– Gene Kim and Steve Yegge, Vibe Coding 2025 [35]

By involving a human in the AI development process, we can detect errors earlier and achieve better results, which is also crucial for safety.

Assigning data and actions¶

Whenever possible, we try to present the agent’s results in an easily accessible way, for example by explaining the reasoning or by referring to the data that supports the model’s reasoning. Although it is difficult to make such attributions robust [36], similar problems arise as before when we ignore additional information as soon as it exceeds our expectations or becomes too tedious to verify. [33]

Additional risks¶

This article focuses primarily on new risks that apply specifically to agent-based AI systems. The usual security risks still apply. However, the increasing prevalence of such systems has led to an explosion in new software. Often, however, they are used by people who have little or no experience with software security, reliability, and maintainability. Therefore, all standard security checks should continue to be performed, as described, for example, for Python applications in our Python for Data Science tutorial [37].

Economic and ethical concerns¶

It would be negligent of us not to also point out general concerns about the AI industry as a whole. Most LLM providers are companies run by tech oligarchs [38] who have shown little concern for privacy, security or ethics in the past. On the contrary, they often support elitist, undemocratic policies.

There are also many signs that they are promoting a hype-driven AI bubble without sustainable business models – Cory Doctorow’s article ‘The real (economic) AI apocalypse is nigh’ [39] summarises these concerns well:

AI is the asbestos we are shoveling into the walls of our society and our descendants will be digging it out for generations.

Ultimately, it seems very likely that this bubble will burst or at least shrink, and AI tools will become much more expensive, enshittified [40], or both.

Conclusions¶

In Bruce Schneier’s article, which we quoted at the beginning, there are some efforts to secure agentic LLM systems, but the hoped-for revenues are at the forefront. The more people use agentic LLM systems, the more and more sophisticated attacks can be expected. Most of our sources only describe proof-of-concept attacks, but it is only a matter of time before we see the first attacks in the real world.

So we will have to keep up to date with current developments, continue reading the blogs of Simon Willison [3], Bruce Schneier [4] and Snyk [41], and publish our new findings on the cusy blog [2].